Listening Well

The plot in every Romantic Comedy is simple. Two hot people meet. There is a barrier that prevents a lasting connection. Time progresses; walls shift. One person puts themself on the line to communicate how they really feel. Sparks fly. Change the actors, flesh out the story, throw in a few jokes, profit.

This isn’t a criticism of the Rom-Com. The formula is part of the reason we enjoy them. (Have you read Pride and Prejudice? It’s fantastic, and I’m comfortable enough in my masculinity to say so. Fight me if you disagree.)

The central plot point in every Rom-Com–most dramas, really–is poor communication. If the characters would just talk openly and respectfully, most of their problems would evaporate. I get it. Being more transparent comes with a potential for both connection and pain. It requires confidence. It is hard, emotional work.

At the same time, good communication is the central challenge in all of our lives. Does your boss really know you? When was the last time someone sat with you and just tried to understand your heart? How much better would your relationships be if you understood what the people in your life truly thought and felt?

Most communication skill education focuses on speaking effectively. And yes, people are more likely to respond favorably when you communicate your wishes clearly. But speaking effectively is only half of the challenge–and probably not the most important half. In my experience, learning to effectively listen does more to improve communication than anything else. Speaking well may get you what you want right now, but excellent listening will help you build powerful, collaborative relationships that support you over the long-term.

The best book I’ve read on the subject is Listening Well, by Dr. Bill Miller [1]. For those who may not know, Bill Miller is the co-founder of a practice called Motivational Interviewing. Motivational Interviewing is an evidence-based method therapists and doctors use to help people choose healthier habits. It isn’t a Jedi mind trick where we instill our values in someone else; it’s a skill we use to draw out intrinsic motivation for change. There is plenty of nuance to the approach, but all Motivational Interviewing is founded on principles of effective listening.

In Listening Well, Dr. Miller synthesizes decades of experience into one hundred focused pages. Each chapter is short, and most include a practical exercise to apply the skills taught. Listening Well is written for a general audience, but I’ve found it immensely helpful in my work and personal life.

Listening Well is written to help you experience accurate empathy–a correct understanding of someone else’s feelings, beliefs, and thoughts. Empathy in this context is not intended to mean an innate shared feeling, nor is it short statements of sympathy like “I’m sorry that happened to you.” Accurate empathy is like obtaining API access to someone else’s mind (with read-only privileges, authentication, and rate-limiting in place, of course). Accurate empathy is a learnable process that allows you to repeatedly guess and confirm what someone else truly means while actively deepening the relationship.

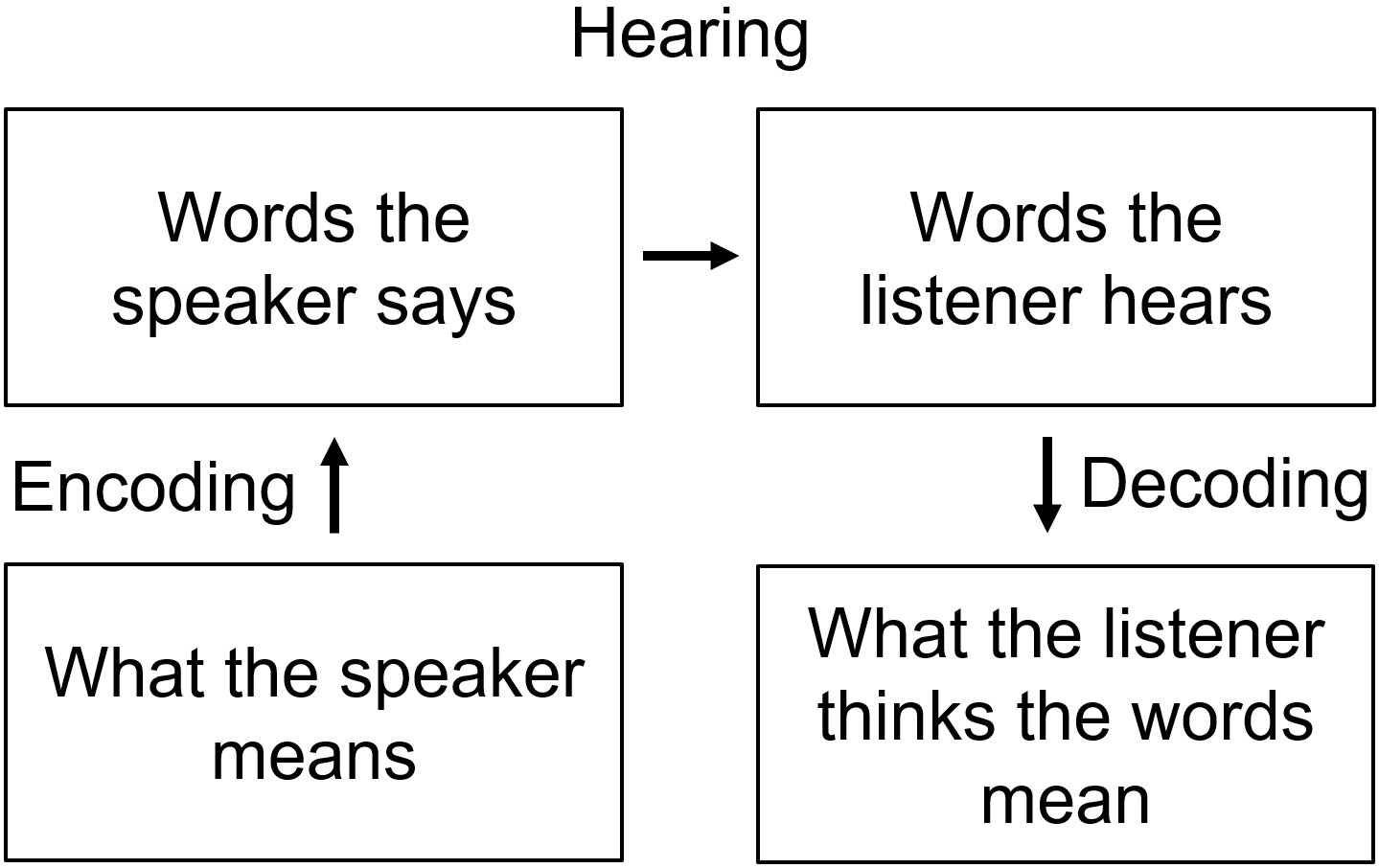

In explaining accurate empathy, Miller summarizes the work of Thomas Gordon, who described a seemingly simple model of communication: the speaker translates what they mean into language, you hear spoken words, and then your brain intuitively interprets the meaning of those words. This process of encoding, transmitting, and decoding happens effortlessly. In addition to conversation, this process is foundational to literature, music, news, and entertainment. We would have not have created civilization without an ability to share our minds so through language [2].

A simplified diagram of Thomas Gordon’s model of communication. Adapted from Listening Well and Motivational Interviewing, 3rd Edition.

But the process of communication is marred by one tragic flaw: the listener often believes they understand what the speaker thinks, even though they cannot know with certainty what the speaker actually meant. This is not a failing of the listener or speaker. Language is ambiguous, complex, and lossy. My brain cannot stop itself from expanding upon what you said, and I’m often wrong. Even if you painstakingly construct seemingly perfect speech, I will misunderstand something you say [3].

You would be correct in reminding me that communication is a dialogue, and that one way speech will always be marked by misunderstanding. This is true, though I offer two important challenges that need to be overcome through dialogue.

First, listeners often assume that they understand what speakers mean. It takes practice, time, and emotional availability to counteract this habit. Even when an opportunity for dialogue arises, listeners may move on before they develop an accurate view of the speaker’s mind.

Second, effectively clarifying what someone means is inherently challenging. In the simplest case, repeating back what you heard can work. Miller calls this a simple reflection, and it is excellent for confirming that you heard what was said. With straightforward instructions, simple reflections are incredibly valuable. Almost every high-functioning system incorporates simple reflection into its communication structures, and it’s an easy way to improve ordering a burger or leading a surgery suite. But simple reflection doesn’t solve the first problem: it confirms what was said; it does not confirm what was meant.

Solving this dilemma is the crux of Listening Well. How do you actively listen in a way that helps you truly understand what is meant? You could focus on asking questions–and you will pick up some skills to create more effective questions in this book. At the same time, questions are emotionally expensive. Asking too many questions feels like an interrogation. Questions can also put you in the role of authority figure, which quickly shuts down open conversation. A great question can make all the difference in the world, but an overly eager questioner is terribly frustrating.

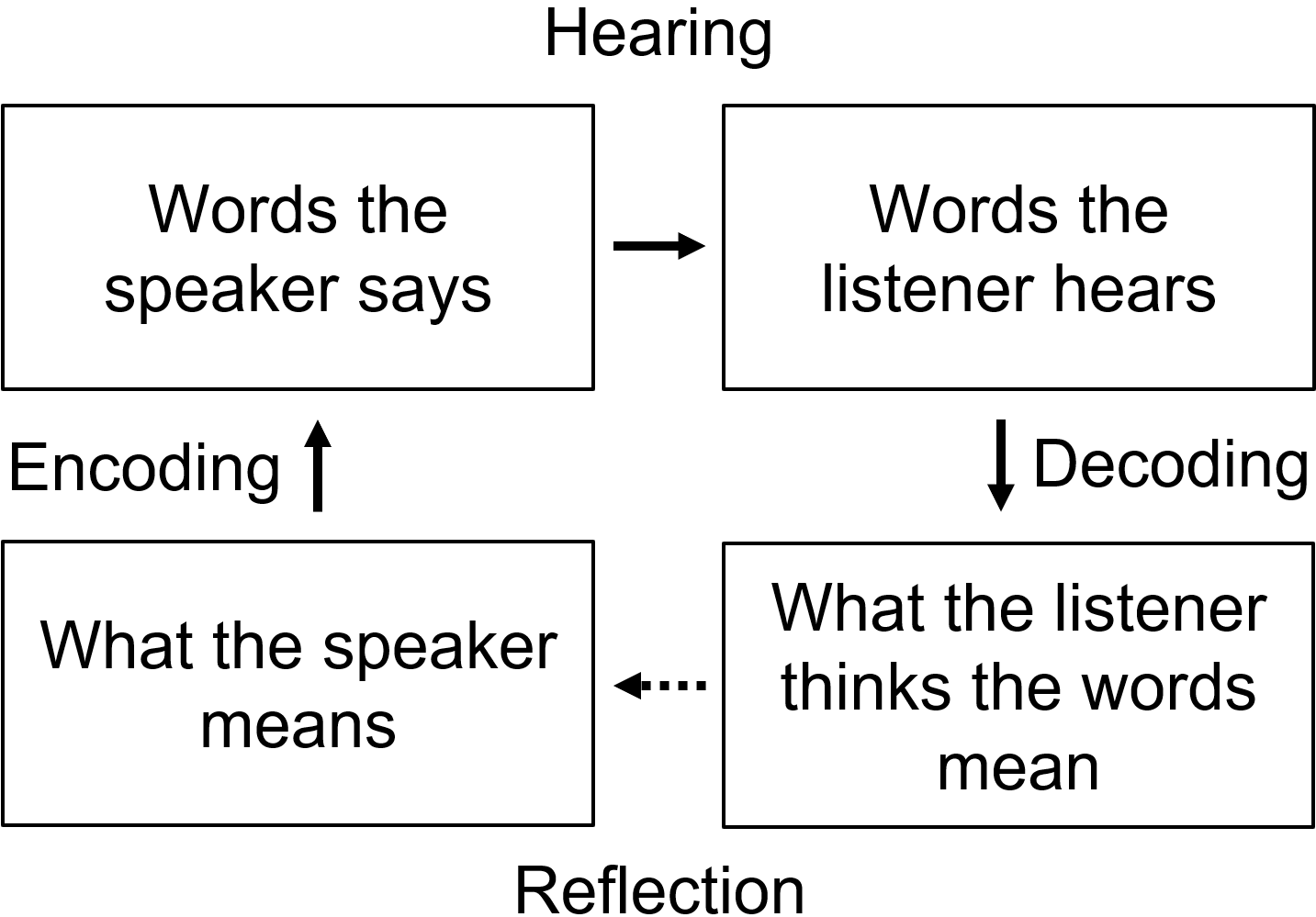

How do you clarify with fewer questions? One solution is the use of complex reflections. A complex reflection is a simple statement that guesses what the other person means. For example, someone might tell you about an unjust criticism they received. “Do you feel angry?” may be answered with a yes or a no. If you’re lucky, the speaker may spontaneously clarify what they meant. On the other hand, guessing “You must be angry” is an invitation for the speaker to clarify what they mean, continuing the conversation. “I’m not angry, I just feel like my efforts have been ignored…” Answering with a complex reflection also shows that you’ve taken efforts to walk in their shoes, deepening the relationship.

Closing the communication loop with complex reflections. Adapted from Listening Well and Motivational Interviewing, 3rd Edition.

A well-formed complex reflection is a nearly free API call. I’ve had people get incredibly angry at me after what I thought was a reasonable question (it’s expected from time to time in my work as an addiction psychiatrist). But I can’t recall any instances where trying to understand someone through a genuine, curious reflection caused more than momentary annoyance. Complex reflections have leveled up my communication abilities more than anything else I have ever practiced. (And I still suck at using them.)

I can’t emphasize the power of complex reflections enough. When I’ve trained novices in this basic skill, It’s not uncommon for them to walk away feeling like they were heard in a way they haven’t been in a long time. (And this comes after they listen to each other, not me!) Does it always work? No. But it is a great tool that will make you more effective.

I’m only giving you a taste of this phenomenal book–but it’s the part I find most insightful. Miller goes much further in expanding on this model, and provides helpful skills around roadblocks to effective listening, applying these skills in relationships, and even a few gems you can apply to speak more effectively.

Most non-fiction books contain 1-2 take-aways which are stretched to fill the 200+ page format. This is not that kind of book. It’s a dense, practical, rich book with timeless advice. I can’t recommend it enough.

Best wishes,

Jeff

Thank you for reading. If you found this post helpful, please consider sharing it.

Footnotes:

[1]: I am using Amazon affiliate links, and will receive a small commission from Amazon if you choose to buy a product from them.

[2]: It is impossible to overstate the physiological complexity underlying spoken communication–even if you take consciousness for granted (which I do not). Neurons somehow condense meaning into conscious language. The speaker then subconsciously coordinates muscle activity to force air across sound producing structures resulting in pressure waves corresponding to distinct phonemes. These waves then travel until they are directed by funnels of cartilage on the side of the listeners head into a tiny tunnel, where these minute pressure changes vibrate a membrane to mechanically conduct a signal into the inner ear. Distinct frequencies are parsed out by cochlear neurons, and these are then translated back into phonemes and language within the brain, where the process of meaning-making can begin to occur. We assume this is normal, but it is one of the most profound products of evolution. Why did I go through all of this? Probably not for you; I personally like to experience the wonder of neuroscience as often as I get the chance.

[3]: This is one of the many reasons why writing is so challenging. The writer tries to anticipate–in advance–the many different directions your brain may go when encountering language. Fiction uses the generative nature of language-based-meaning-making to stimulate emotions and imagery, while technical writing tries to limit your mind’s ability to wander.

[4]: There is no [4] in the essay. But I’ve added this brief note because this is only my third post, and I’m sure someone is wondering what this has to do with sex, drugs, and suicide. First: this is my mental health blog, so I get to talk about whatever the hell I want to! 😊. (Of course, suggestions are always appreciated, and I’m currently writing about a sexually adjacent topic for next month.) Second, and more importantly: I’m a firm believer that our interpersonal relationships are major drivers of all human processes. If improving your ability to communicate doesn’t improve your sex life, I don’t know what to tell you. You simply cannot understand without discussing the interpersonal model of suicide, and as for drugs—well, you get the picture.